Everybody got some favourite albums. Music that accompanied yourself through difficult times, records that acted like a friend when there was real one around. Whether it was the sound around the times of your first kiss or the starting point of your own attempts to take a deeper look into new musical territories. We all have this record somewhere in our hearts and private collections. In this category NOTHING BUT HOPE AND PASSION lets the artist’s do the writing as they share their personal stories and feelings on their most loved record with us.

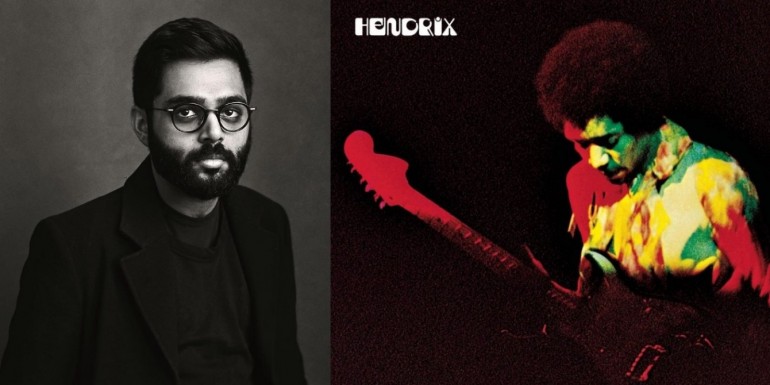

We know that it can be horribly hard to name exactly one favourite album. Maybe it’s less about having one specific favourite album but more about the music that changed your life and made you head into a new direction. Rafiq Bhatia of SON LUX found that sort of record in a legendary live album by the one and only Jimi Hendrix. Bhatia and drummer Ian Chang joined SON LUX founder Ryan Lott for his latest album Bones, now making SON LUX officially a full band. NOTHING BUT HOPE AND PASSION present the band’s forthcoming German dates this October, so don’t forget to grab your tickets

Jimi Hendrix – ‘Band of Gypsys’ (1970)

I’ve always felt that there is a story in each and every note that Jimi Hendrix played during his two Band of Gypsys concerts at The Fillmore East, which took place during the very first moments of the 1970s. The first time I heard this music was after a chance purchase of the concert DVD. I was in high school and newly obsessed with Hendrix’s studio albums, and I guess I was just hoping for something that would live up to what I’d already heard. Needless to say, I wasn’t prepared. As intrigue gave way to obsession, I found myself watching the footage night after night for weeks, right before falling asleep. The effect has never really worn off.

More than any other recording I’ve heard, these tapes reflect Hendrix’s uncanny ability to express something universally human through his instrument, and to do so in a way that shatters the limitations of other forms of human expression. It’s as though Hendrix makes the guitar ooze the stuff that memory is made of and molds it into the shape of arrowheads. These meticulously articulated shards of sound hit directly in the solar plexus, somehow penetrating deeper than language ever could. As their resonance reaches the spine, it sends shockwaves through the most fundamental levels of our experience, like a hammer to consciousness’ funny bone.

The songs, many of which were unveiled here for the first time, signal a transition into a more outward-looking, activist humanism, one that was sadly never fully realized before Hendrix’s death later that year. It’s visionary music, illustrating paths towards a human ideal (The Power of Soul, We’ve Got To Live Together) alongside portrayals of the dystopian present (Machine Gun). Actually, perhaps ‘illustrating’ is an understatement; in Hendrix’s hands, the guitar quite literally renders a sonic image of everything from human jubilance to instruments of war. A stoic, unwavering focus on the music itself largely replaces the flash and trickery that defined earlier performances, but there’s still plenty of visual drama in his facial expressions. When words are involved, they take a supporting role, like an outline lightly sketched for easy redefinition.

More than anything else, I hear the sound of striving in this music. The goal always seems to sit somewhere beyond Hendrix’s (terrifyingly immense) personal capability, or perhaps beyond any individual’s capacity. Almost half a century later, it remains an essential roadmap for anyone interested in exploring the outer limits of what human beings can do; I highly recommend the journey.