Although I was totally late to the party, I still remember very vividly the moment when I first held Coldplay‘s fourth record in my hands. I had spotted Viva La Vida Or Death And All His Friends in a CD stand beside my school friend’s stereo and prompted him to give it a spin for a very specific reason: the third single from that album, Lost! had been playing on TV regularly as a live video and I had been intrigued to find out what the studio version sounded like. Content but not thunderstruck by the version I heard, I still borrowed the CD to give it a proper listen at home.

Up until that point, I had never paid particular attention to albums. Back in 2009, ripping songs from YouTube or file sharing networks in awful quality was still a thing, and my musical horizon was yet confined to the singles you heard on the radio. Even the elaborate release campaign for Viva La Vida – Coldplay’s first single Violet Hill was available as a free download for seven days, a radical move at the time – barely grazed my sphere of consciousness. Although having started to play the guitar a year prior, putting in the money to download an entire album on iTunes or even buying a CD in a store seemed like a very distant thought. Listening to Viva La Vida at home, however, I quickly realized what I had missed out on. As the sounds of Jon Hopkins‘s Light Through The Veins (which you should totally enjoy in its full beauty as well) faded into the Indian-style instrumentation of Life In Technicolor, Coldplay pulled me into their microcosm and exposed me to a listening experience that profoundly changed my way of looking at music.

The thought of a Coldplay album sparking interest in music might appear ludicrous to someone who either grew up during the indie explosion of the early 2000s or has only ever heard the bubblegum pop the group released during recent years. But back in 2006, when the band started work on their follow-up to 2005’s highly successful third album X&Y, Coldplay were both on their way to becoming the biggest rock band in the world, and being ridiculed for their inoffensive, melodramatic delivery and lyrics. Anxious to forever be labelled ‘the most insufferable band of the decade’, as the New York Times wrote in their review of X&Y, the band retreated to a self-built studio in North London. There, they teamed up with Brian Eno, who at that point had not only collected accolades on merit of his own music, but had produced several albums by U2, a band Coldplay were often compared to at the time.

It quickly turned out that Brian Eno was not only able to give the band’s sound a badly-needed refreshment, but he also unleashed creative powers in its members that seemed to have laid dormant previously: Cemeteries Of London, the album’s second track, paints a gloomy picture of Victorian-age London in rough brush strokes, while wafts of sounds and handclaps swirl around Chris Martin’s words, all backed by a frantic rhythm. On Yes, Martin croons in an unusually low register about unhealthy, perhaps illegal desire, accompanied by Davide Rossi’s virtuosic violin playing. When Coldplay sourced stylistic elements from earlier albums, they did so with a delicacy, as not to damage the intricate balance of Viva La Vida’s pacing: Life In Technicolor, arguably the most cliché Coldplay song, was stripped from its vocals and repurposed as an album opener, the anthemic Lovers In Japan was placed at the heart of the record, with a tender piano ballad called Reign Of Love tacked to it.

Appreciating the album concept

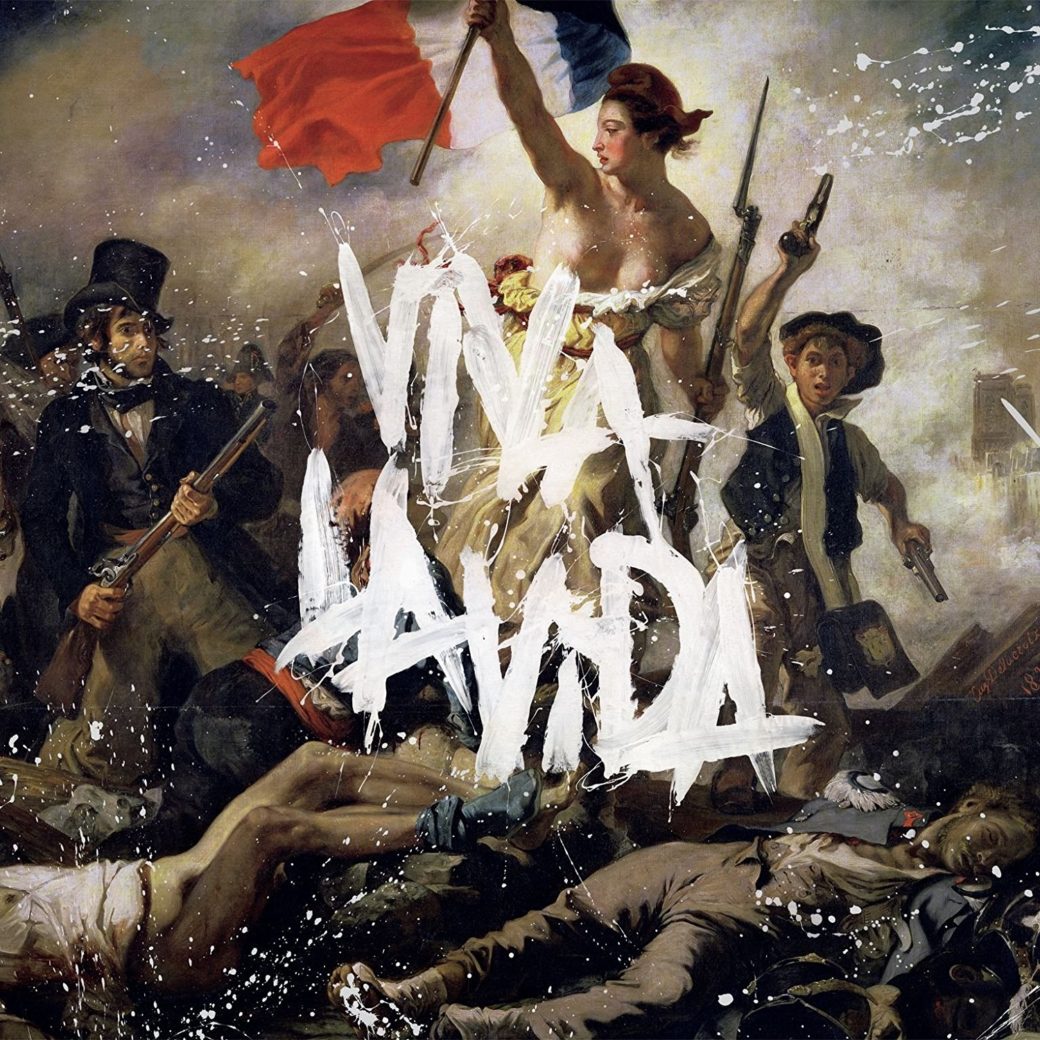

Viva La Vida worked so well as a record precisely because it was composed to work like one. While the individual songs served to showcase different facets of their new sound, sometimes disparate parts or even whole songs were fused into one track and transitions carefully laid out to make the tracks flow into each other seamlessly. Together, they managed to paint the moody, sinister, but also hopeful and sparkling counterpart to Viva La Vida’s cover art. Using Eugene Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People, Coldplay conveyed both the frame and the visual complement to the album’s hugely successful title track. But they didn’t stop at that: Expanding on the design of X&Y, the band not only crafted corresponding stage designs and cover artworks for their singles, but also wore costumes that pointed back to the revolutionary figures Delacroix depicted.

It was the immersive design of the Viva La Vida album cycle that invited me to discover all the intricacies of their music: as mentioned previously, Martin mostly forewent his trademark of heartfelt, but at times overwrought lyricism for a more oblique style that invited more than one thought about their precise meaning. His chiming acoustic guitar strummings prompted me to discover quite a few unusual guitar tunings and chord shapes beyond the ones commonly used to accompany campfire sing-alongs. Several songs on Viva La Vida experimented with unusual song structures, time signatures or chord progressions.

But most importantly, Coldplay introduced me to a new kind of musicianship: it didn’t matter if you could play a blast beat on drums or shred a guitar solo like Jimmy Page. Their music appeared easy on the ears, but once you zeroed in on its musical components, you started to discover how well-thought-out and not at all poppy those songs were actually composed. Viva La Vida required not virtuosic playing, but creativity and an ear for sound to be composed and produced: in short, it was easy to play, but hard to reproduce its sound and magic. And given all that, it still was very much an anthemic pop album, one that had a lot of lessons to offer for a burgeoning, young musician like I was.

Coldplay served as a gateway into all sorts of different directions – the albums of such disparate artists like Radiohead, Arcade Fire, Phoenix or Karkwa, or even the engulfing shoegaze of a band like The Twilight Sad became palpable to me after having listened to and obsessed over Viva La Vida and all its predecessors in full. However, it also set a precedent: for years to come, the ideal of the band, the creative collective that embarks on creative endeavours together, became an incredibly powerful notion. And I would only very hesitantly approach any genre that strayed away too far from the formula of ‘band music’ – hip hop, techno, house, electronica – seeking the live immediacy of rock music without fully understanding those styles until much later.

In the meantime, Coldplay departed from the idea of being the best rock band in the world, and settled on becoming the biggest. Both their sound and themes became less equivocal and more straightforward, and in doing so, the intricacy of their sound slowly started to fade away in favour of more pomp and saccharine production. Paradise and the Rihanna-featuring Princess Of China from their next album Mylo Xyloto were early signs of what the band was really up to – by the time Coldplay released a track with Avicii, I had long lost interest in the course of the group. I now look at it as a crossroads of sorts: at a moment where I was just discovering the magic of ambitious rock music, the band had already moved on to competing with Justin Bieber and Black Eyed Peas. At the time, I used to lament the loss of the band I so deeply cherished. But now, I look back at Viva La Vida knowing that it is the reason why I ended up here in the first place.