CHRISTOPHER OWENS is an absorbing and enigmatic character, to say the least. His backstory reads like a fantastical plot for a novel; raised in a travelling religious community/cult, The Children of God, his childhood saw him swept up and carried across Asia and Western Europe like a tiny piece of driftwood. At the age of sixteen, he left the church and skipped the shores to Texas, working a spectrum of menial jobs until his path intertangled with that of artist and oil tycoon Stanley Marsh, who took him on as a personal assistant and, in a broad sense, threw open the doors. Heading to the coast of San Francisco after nine years in The Lone Star State, he spent some time playing alongside ARIEL PINK and, at the age of 28, began to write his own songs. Since then he’s been at the bow of pop starship GIRLS (until their somewhat stormy disbandment), dabbled in modelling and branched off into a solo career.

CHRISTOPHER OWENS is an absorbing and enigmatic character, to say the least. His backstory reads like a fantastical plot for a novel; raised in a travelling religious community/cult, The Children of God, his childhood saw him swept up and carried across Asia and Western Europe like a tiny piece of driftwood. At the age of sixteen, he left the church and skipped the shores to Texas, working a spectrum of menial jobs until his path intertangled with that of artist and oil tycoon Stanley Marsh, who took him on as a personal assistant and, in a broad sense, threw open the doors. Heading to the coast of San Francisco after nine years in The Lone Star State, he spent some time playing alongside ARIEL PINK and, at the age of 28, began to write his own songs. Since then he’s been at the bow of pop starship GIRLS (until their somewhat stormy disbandment), dabbled in modelling and branched off into a solo career.

A New Testament is Owens’ second musical offspring since stepping out alone, and the trajectorial shift – from 2013’s Lysandre but especially his early work with GIRLS – is apparent. His lungs have opened, and he’s worked into his own voice like fingers pushing into a glove. In terms of sentiment, the sun has swooped in to pick him up from the dark corners of Broken Dreams Club; while certainly not bereft of sadness (Stephen, for example, deals with the tragic infant death of his older brother), the more recently-written pieces are drenched in optimism. Perhaps most obviously, in Key to my Heart, the outspoken romantic has found his balancing half. It’s all washed over with waves of unabashed country influence; a strangely gorgeous sonic bubble that reads like an extended diary entry.

As we sit down to talk, OWENS is immediately compelling. Stirring a mug of tea, he speaks thoughtfully, moving the words about in his mouth as if to taste them, and his candidness is refreshing.

I guess the first thing I wanted to ask you was about your songs, as individual entities. How would you describe your relationship with, or attachment to them? I know that some of the songs on this record were written up to six years ago; you seem to hold onto them for a long time.

Oh, yeah. Have you ever watched Harry Potter?

Sure.

You remember there’s this thing that Dumbledore does, where he takes his memories with the wand and puts them in the bowl, and he saves them? It’s like that. They’re like a piece, they’re a part of me. You can’t hold them, but they’re there. I think songs, they ultimately come from everything in your life. You listen to thousands of songs and they go into your brain – maybe you don’t remember everything about them but they’re in there, and even lyrics too, other people’s lyrics – and then in your subconscious you’re making an algorithm, essentially. When you go to write a song, it’s all of those other songs coming out – this piece of that one, this piece of that one – and making your own. Kind of like when you dream, it’s all stuff from your real life, though it’s your subconscious. So it’s like daydreaming. Songwriting is daydreaming.

What’s the experience of releasing your songs to the public, then?

I enjoy it. I don’t get nervous. I hear people talking about being nervous or shy about it, or ‘oh, it’s difficult.’ For me, it’s thrilling. It’s the most fun part, I think. I love it.

I’ve heard that you have a whole spectrum of songs tucked away, just waiting for a time when they may be released. How do you keep track of them all, and decide when things are ready to come together?

Well, I’m kind of a whimsical writer. I wait for the idea. I’ll just go about life and I’m one of those people that’s like ‘ooh, I’ve got an idea!’ and I have to go and do it. As opposed to something that I envy a lot, people that have this thing: ‘I write in my study from this time to that time.’ I think that would be great, but I can’t do it. So, I record them on my phone, and then later on I’ll get the guitar and flesh it out, and then I’ll record that, save it on the computer, put it away. Then it’s really about when you get the next chance to go into the studio. When you have the time, and the budget, and it’s all planned. It seems to happen once a year, which seems like a good structure to me. When I know I have the opportunity to record, I just go and look at all of those songs. The idea [with A New Testament] was to try to do a country-influenced thing, so you have to look – okay, which ones could be country or which ones are country…

So that was something deliberate that you set out to do with ‘A New Testament’?

Yeah. It’s something I’ve been wanting to do for a long time. I like country music.

Going back to GIRLS, in the past you’ve talked about how you wanted the band to feel like a family, an all-encompassing, everybody-growing-together thing, and that the disfunction of that was perhaps one of the key reasons why the band didn’t work out. What does family mean to you?

That’s a difficult question, because I don’t really have what I think a family is.

What do you think a family is?

I think family is, whether you like it or not… you’re entangled, you know. It transcends things like love and hate, it’s something deeper. For a family, there’s the opportunity for a deeper understanding of each other, because you’ve spent your lives together. Families should be a unit, ideally. I guess there’s probably all kinds of families that yell at each other, that shoot one another, but ideally I think family is something fantastic. You see it with animals… Sometimes. [laughs]

In terms of a band, then, do you think it’s possible to create family in that way? Was it was a realistic or achievable ideal to have?

I’m kind of an all-or-nothing sort of person. I think a band should be… like a gang, you know. You would break your morals for the other person, because they come first. Unconditional love, and that sort of thing. Also, a band specifically, because it’s a creative thing, unlike a gang, everybody should be a part of that creative process. I think a band should be presented as a band; I don’t like this thing that was going on with Girls, where it was me and JR in the photos, and everybody else that we were recording the album with or touring with was presented like they didn’t exist, like they were disposable. I feel like I’m calling things as they are now. I’m working with almost all of the same people. There’s some of them that have quit in the past and said ‘I don’t wanna be a part of this shit,’ you know, they were really frustrated in Girls. Or you start having interpersonal problems with people. I didn’t really say much, but some of the others started fighting over little things. This is me taking me material and asking people: ‘do you want to be a part of this project?’ And it seems to be, for me, more realistic. For them, more doable. Yes, I’ll make an album with you, we’ll tour it together – and then we’ll see. They all have their own things going on, so it’s more ideal for them, I think, too. And they know it’s not a given. I think it’s nicer to be asked: ‘Oh yeah, thank you, yeah I’d like to do that.’

Has deciding to go solo meant letting go of some of those previous expectations?

Yeah. Basically what I did was let go of the idea of having a band. I kind of just starting working the way that seemed to be working best. But also, I enjoy getting to present the songs under my own name. You know, it’s like Elliott Smith or Jeff Buckley or Paul Simon, you have a whole history of this. Years ago, I remember starting to be like… I feel more like one of these guys than somebody in a band. That’s really just a gut feeling, that’s pretty much the main reason. I also found myself a little bit more, you know? I want to be like a Randy Newman or something, work with all kinds of people over the next however many years I last, and make my songs. There’s something great about writing personal songs, which I’ve always done, and presenting them as yourself. It’s just a nicer feeling.

One of the lyrics that I found particularly moving on ‘A New Testament’ were those to ‘Stephen’, in which you describe losing both of your parents in different senses; your father physically and then your mother emotionally, after the death of your older brother. Keeping this open-ended, how have those relationships morphed over the years, or where do they stand now?

It’s funny, because you can want stuff really bad, but things are what they are. Now I know my Dad, where I didn’t growing up, and I like him. My Mom has also left The Children of God and is a regular person now, and I’m in contact with her all the time. I’ve always liked my sisters. Oddly enough, we all live in different places. So we don’t see each other as a group, I see them individually, here and there. You can’t fake certain things. It’s like, there’s a reality of the relationship we’ve had and the things we’ve been through as a family and, you now, our family unit was really… In the Children of God, oddly enough, the next name they picked for themselves when they changed their views and image [laughs], because things were going really badly, was ‘The Family of Love.’ And then that got really weird, that was maybe the weirdest period…

When was that?

I think they did that in like ’78. So then they changed some beliefs, and the name as well, to just ‘The Family.’ So, the silly thing is that in The Family, they didn’t believe in family units. People were not married to each other. They were ‘mated,’ that was the closest thing they had, but even most of them weren’t even that. All adults, you were supposed to treat like your parents, and all the kids, you were supposed to treat like your brothers and sisters. And, it sounds like something where you would know the difference, but… If you’re born into that setting and you spend up until the age of sixteen there, it sets in. My relationship with my sisters is pretty much all from my adult years, because we’ve made an effort, you know? But other than that… They really effectively destroyed family units in this group called ‘The Family.’ And I guess it makes total sense, actually.

‘The’ Family…

Yeah.

When you first moved to Texas, you spent a number of years working mundane jobs, and you’ve said in the past that it was maybe a period of depression for you. How did you get out of the rut, and what role did music or art play in that, if it played one? I guess I’m thinking of all the other people out there who are stacking shelves and working these crappy jobs, but might aspire to something else.

Yeah… Ugh. It was about five years where there was no alternative. It took a little bit of magic, you know. I met somebody, and he was a very successful person, a businessman essentially, but he also made art and he would hire people to help him make his art, and I got hired on in a sort of temporary fashion and we would talk and we were both kind of fascinated with each other, and he ended up giving me a permanent job in his office. Our lives were very entangled. I was looking for a worldly education, just to understand the simple things about how the world worked, why things were the way they were. Or just to know about how things worked, not necessarily why but how. [sighs] And I was looking for stability. To have someone of that age who I could tell anything to, it was like having a father for the first time in some ways [laughs]. But it wasn’t really a parental relationship. It was very unique. I think it’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing that happens.

Are you still in touch with him?

He just died, about a month ago. Yeah [pauses]. But you know, I think opportunities like that come up for people. A lot of people might be scared, might be inclined to not take them. But if I had not taken that opportunity I don’t know who I would be right now. I was very angry, I was young, I had come from this horrible upbringing, which I can now appreciate a little bit, but then… no way, you know. I blasted the most angry kind of music, I was just that kind of person. I was very angry. And he… It’s not the kind of thing that you can argue with a teenager about, but he was like “you’re right about this, you’re right about that, it’s true, the world’s like that”, but then, through example, I started to see that he knew something I didn’t. And he would just simply tell me: “if you focus on everything you’re angry about, it’s going to consume your life. You have to choose where you want to focus your energy.” Simple things like that, that I needed to hear from somebody. And we’d make art together, read poetry… I can’t pick or pinpoint any one and say that it’s what made life better, but the thing as a whole, having somebody like that, that actually cared about me, for the first time ever… It felt very good [laughs].

Speaking of people who care about you, in ‘A Heart Akin the Wind’ you talk about this simultaneous desire to settle down and also this almost involuntary urge to keep moving around. You’re in a long-term relationship now, right? How do you think that balance will play out in the next little while?

Yeah, I mean… Travelling has always been a part of my life, and it’s funny, because now it is again. I enjoy it, too. But yeah, there will come a time when I probably will want to spend a bit of time at home.

Where is home?

San Francisco, for sure. For example, something as silly as this, my fingernails [bangs hand on the table]. I use them to play the guitar, and it’s a special way of playing the guitar, and it’s very important to me, my fingers have looked like this forever, just on one hand. It’s kind of a weird thing. I don’t want to say this, because it sounds extreme.

Say it!

For example, if my girlfriend was to say, you have to cut your fingernails or this isn’t going to work out, I would have to walk out the door! That’s not a realistic scenario, because first of all she wouldn’t do that, second of all because… I may actually cut my nails, but you know what I mean. I want to make an album every year. I don’t really have any other skills or anything else that I excel at, so I want to have this as a career, which means I have to tour, because people don’t buy albums. Or a handful of them do. So this is the way it is. But I’ll figure out a way to make it work, I’m confident of that.

Touring, is it something that you would still definitely do otherwise? If people did buy albums?

Yeah. I just don’t know if I’d do it as much. It’s a fun part, but you end up touring a lot. Then, you know, you do things in between. In the past month, my life has turned from being at home all the time to shooting a video, going on this press trip, the tour’s coming next. It just sweeps you up.

What was the sentiment or intention behind calling the album ‘A New Testament?’ It’s got some significant religious attachments.

It’s a little bit cheeky [laughs]. It’s a bit sacrilegious, in some ways. It’s not like one of these bands that calls their album ‘Jesus’ Rotting Head on a Stick,’ some Norwegian death metal band or something. It’s just a bit of fun. I like taking things that people already know and putting my spin on it. It’s also, just very literally, if you take away all the baggage, a great name for a new album. An album should be a testament. It’s like a photo album or something. It should contain information, and part of you.

What’s your testament to?

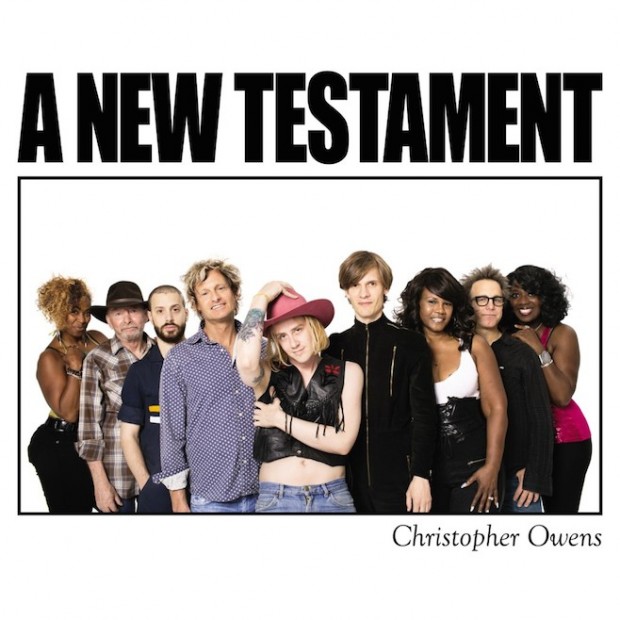

To what I love about music, you know. I’m having a good time. To the people that play on it, that’s why they’re all on the cover. It’s a testament to the group that came together. Also, I’m still here, you know… [laughs]

[one_half last=”no”]

[/one_half]

[one_half last=”yes”]CHRISTOPHER OWENS

A New Testament

Release-Date: 29.09.2014

Label: Turnstile

Tracklist:

01. My Troubled Heart

02. Nothing More Than Everything to Me

03. It Comes Back to You

04. Stephen

05. Oh My Love

06. Nobodies Business

07. A Heart Akin the Wind

08. Key to My Heart

09. Over and Above Myself

10. Never Wanna See That Look Again

11. Overcoming Me

12. I Just Can’t Live Without You (But I’m Still Alive)

[/one_half]

—