McKinley Dixon’s music is characterized by a high level of introspectivity. It’s deeply personal and grabs your attention right away. The audience is not just a passive listener but a friend, foe, and confidant, all at once. Describing his approach to storytelling, Dixon explains: “Ultimately, my music is meant to be a conversation with myself a lot of the times, but also with the person that is listening”. This open channel communication is already palpable on his first release Who Taught You to Hate Yourself?, published on Soundcloud back in 2016. On this record, the then-21-year-old seeks to investigate patterns of internalized self-hatred as well as other symptoms of Black trauma. The album bursts with the keen enthusiasm of a youngster rapper breaching into the realm of inner reflection; eager to experiment with different musical styles and narrative techniques to explore the complexities behind this ‘self-hatred’.

Where this debut is loud and aggressive, it is also contemplative and sympathetic to the initial question. To get a glimpse into the intricacies behind the album’s theme of institutionalized hegemonic structures expressed in internalized self-perceptions is an Atlassian boulder to crack (or rather carry). Dixon kept this investigation close to his own experiences with loss, fear, and love. However, he does not want to be a mouthpiece for everyone who experiences the particular things he describes. He tells me: “People ask me about these traumatic events because they think I talk about in, like, the voice of all people. When in reality I am explaining my family, showing what they are going through.” Dixon rather wants to highlight the connectedness we can find in each other’s pain; how we are able to relate all the more strongly through this shared bond of similar experiences.

Roots

This message is exemplified in the subsequent follow-up The Importance of Self Belief in 2018, on which Dixon laid heavy emphasis on the healing power of community. I asked him how and who he would classify as family:

“There are a lot of different ways to view [family]. For me, it is those that take care of each other. [A] lot of my folks are Black, Brown, queer, trans folk, you know, where family is chosen. I love my mama, my grandmama, grandfather, […]. I have those people in my life, and my sister, but for a lot of my friends and community, they are chosen. I didn’t start seeing it like that until I got a little bit older and realized that blood isn’t necessarily family. It’s really so who uplifts you and who you uplift.”

His answer enveloped the core themes of this record especially, but it also gave me an insight into how he as a person navigates through his life and music. This sentiment of uplifting the people around you and being in turn uplifted by them weaves itself through his entire track record. His first studio album For My Mama and Anyone Who Looks Like Her came in 2021. As the title suggests, it forms a love letter to his family and anyone who can relate to the struggles and joys he describes. The album takes us on a jazz-filled ride of Dixon’s observations and contemplations about both the major and minor moments that can make and change a life. It’s an album where the harsher tracks with more assertive declarations of frustration, like “Never Will Know” or “B.B.N.E.”, go hand in hand with the underlying love apparent in tracks like “Bless the Child” or “Mama’s Home”, for example. On this record, Dixon doesn’t shy away from talking about his more traumatic experiences and celebrating the wonderfully intimate moments shared between family and friends.

Toni Morrison and the Harlem Renaissance: A Little Literary Digression

The investigation of the beautiful and the ugly found in life defines Dixon’s newest release as well. The title of the album as well as the closing track are inspired by three of Toni Morrison’s novels, Beloved (1987), Paradise (1997), and Jazz (1992), respectively. Explaining his decision to name his album in Morrison’s vein, Dixon says:

“Toni Morrison is the best because she’s able to show you how complex love and loss is. She shows that there’s beauty and horror within love and that makes it still love. And I think that, for me, is just chasing a way of describing human complexity. […] It’s easy to make things black and white but it’s hard to sort of show you the duality of it all. She does a great job and that inspires me.”

Morrison’s novels deal with the Black experience through the lens of different time periods in the United States, with the question of memory, collectively and individually, being an essential element in these stories. The stories also feature the theme of Black trauma to access this social plane of identity.

Beloved (1987), for example, is set in the 1850s to 1870s in Ohio and centers around the multi-layered destructive power of slavery, as well as the dysfunctional family dynamics shaped by Black trauma. The dire circumstances the main characters must live by and the desperate choices they have to make, ranging from escaping a plantation to filicide, emphasize the unbalanced hegemony inherent to these power structures.

Paradise (1998) tells the story of Ruby, a town whose 360 Black residents have chosen to live in isolation to uphold their ideal of a city free of crime and racism. However, this ‘utopia’ is set in stark contrast to a new form of racial discrimination against light-skinned Black people as well as the persevering sexism the women of the town have to suffer under. With Paradise (1998) being set in the 1960s and 1970s, the Black Panther movement is also discussed, as the young people of Ruby are very infatuated by it. For the older generations, this threatens their utopia. This culminates in the killing of nine women of a nearby convent who were scapegoated, in order for Ruby to return to its former glory. Paradise (1998) showcases the danger of a moral high ground veiling nothing else but frustrations and violence, and how the most vulnerable of society often suffer the most.

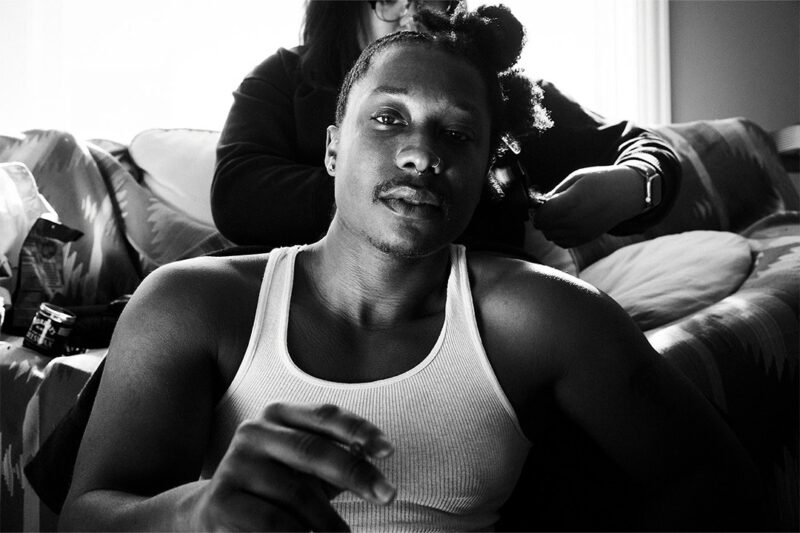

Photo by Jimmy Fontaine

Jazz (1992), on the other hand, chronicles the relationships of different characters living on the East Coast in the 1920s. With the setting of Virginia and New York City, specifically Harlem, the story of a love affair between a married man and a young woman, and the entailing consequences, transpires in Morrison’s vivid rendering of the Harlem Renaissance in its prime — a time when the outpour of Black art was at an absolute high. The Harlem Renaissance was the first artistic and cultural movement that centered on Black artists, with a second, European wave soon to follow in the form of the Négritude in the 1930s, this time localized in Paris. Both movements aimed at the establishment of a (global) Black consciousness as well as the rebirth of the Black arts. From dance, theater, and literature to art, fashion, politics, and of course music, they encompassed a broad range of the fine arts and endowed them with social urgency. The cultivation of these higher art forms was meant to raise a sense of community, to showcase their worth in their own right, separate from their White counterparts. Echoes of these messages are found in the following movements, prominently in the Civil Rights Movement and its akin energy in the creation of art and music. In a similar vein, Dixon tells me:

“The Harlem Renaissance was such a specific time in everybody’s life that is Black. It’s important to have those dates in time. It’s all about family and community. You sort of meet people, and you never leave them. It’s easy never leave somebody if you really are trying. And I think that not only is musically but also in real life.”

But let’s get back to Jazz (1992). As the title suggests, music, especially jazz, shaped not only the musical aspects of the novel but also the narrative structure of it. You can never quite rely on the voice narrating; it focuses almost only sporadically on chronologicity and rather contemplates the beauty and derangement of the city. The described entangled web of people looking for love, acceptance, and kinship depicts a search that ends for many of the protagonists with rejection, violence, and even death.

In all of these works, Morrison utilizes these tragic fates to juxtapose the extremes of love and pain in a society regulated by an axis of race, and in turn, showcases the inherent connectedness that Black trauma can encompass, as well as its ambiguous role in the creation of memory and thus for the construction of identity.

Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!?

For Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!?, Dixon wanted to similarly emphasize the ambiguity of these factors. Yet, he further clarified to me that he did not intend to center on the aspect of Black trauma on this record:

“Black trauma is very complicated for me because I used to look at it in the sense of ‘Black trauma makes records sell’. People sort of love trauma porn, right? And for me, that was my last record. It was like really coming to terms with what trauma is […]. But then this record, it’s this thing where it’s like: ‘Trauma is not something that keeps you up forever’. It sort of evaluates you. You go through it, and you keep moving. It changes. And I think that this record is more: ‘Trauma doesn’t keep you locked in one situation’. Whether that’s mentally, physically or literally. Trauma is something that you do, that never goes away. But that’s not good or bad – that’s just life.”

Trauma, or here specifically Black trauma, may influence how we connect with people or the decisions we make, but we are not defined by it. Rather, it is a factor in life, whose limits we must learn to recognize but also realize how to live with until we may be able to overcome them. But until then, it is up to us and the people around us to come together and help each other heal. How this healing may look, can be as individual as the traumata themselves, but for Dixon, it is directly tied to communication and collaboration. It’s about making people feel comfortable to share, both emotionally and musically. The spirit of collaboration on this record – and all of his before-mentioned work for that matter – is essential to him: “[T]hat’s sort of how I go about all of the people who are working on my music because it’s just so easy to make somebody feel comfortable in their space. It brings everybody’s own personal identity into it. If I want to make a song that is a conversation, a way to make a conversation happen is to be vulnerable. And a lot of it is [about] how you make people feel comfortable and that’s also how you have a conversation that goes back and forth.”

Remembrance

Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!? forms a story of remembrance. Of the good and bad, the beautiful and the ugly. Conceptually, the album resembles “a coming-of-age movie”, Dixon explains. “The album itself is set up as like one day, one summer – this is what we did when we got in the car, and then it goes from there.” With his background and interest in animation, Dixon’s cinematographic approach to storytelling is evident in both the brevity and intensity of the album. At a runtime of only about 29 minutes, Dixon accomplishes to tell us about his deepest fears and highest aspirations for himself and the people around him. Commencing with a reading by writer, poet, and critic Hanif Abdurraqib of an excerpt from Jazz [1992] about the contrast-rich atmosphere of 1926 Harlem, the album’s core themes of memory, family, love, and loss are captured in Morrison’s description of a city filled to the brim with contradictions. With vibrancy and allure, but also violence and atrophy. Dixon ties his stories into this rich tapestry of opposing impressions that in reality are deeply rooted in the shared experience of a US metropole like NYC or Chicago.

Photo by Jimmy Fontaine

Over the course of the album, Dixon offers us a piece of his own as well as the people he wishes to commemorate in every narrative. The album shines with its orchestral instrumentations, where the line between classical and jazz music is wonderfully blurry. It is loud and harsh and impassioned where it needs to be while providing us with slower but no less intense breather moments. Dixon pursues stories of longing and perseverance in “Sun, I Rise”, of violence and lost childhood in “Run, Run, Run”, frustration and rebellion in “Mezzanine Tippin’”, and the pain of losing a loved one, in all its ugly and beautiful facets (or stages of grief if you like), in the incredible “Tyler, Forever”. Honoring Morrison’s influence, Dixon incorporates many Black art forms on this album – beginning with Abdurraqib’s spoken word reading of Jazz (1992) to the more obvious hip-hop and rap, to the most prominent jazz elements present on the tracks. Whether or not it was a conscious decision to incorporate them like this, Dixon answered: “I don’t really seek out these sorts of things. It sorta becomes just how I think. Black art forms are so automatically rhythmic that it is easy to connect Jazz with Punk and it’s easy to make rap music into a punk song. All of these things are just so interconnected because they all deal with keeping your ears to the street.”

Looking Back and Moving Forward

These stories culminate in the closing track “Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!?”, where Dixon captures the bittersweetness of the feeling that is remembering the people we’ve lost and loved so, so much. From Dixon’s narration and Ms. Jaylin Brown’s marvelous vocals to the amazing brass featured, the song concludes this album so beautifully – both thematically and musically – that the consequent looping of the album is just so easy to do.

“I think as a Black person you sort of can already see what’s next because we are so used to existing within the past, present and future. We sort of have to evaluate everything in our lives just to move forward and that includes looking back. But I think it is knowing your past [that] sort of leads you real’ easy into your future.”

Personally, the narrativity and cinematography of the album as a whole remind me of a jazz musical that could have been released now or 90 years ago. The stories impress in their validity as alone standing narratives as well as the album’s potency as this grand narrative about the Black experience of a millennial Black man living in urban America. I share his assessment that his roses cannot come soon enough:

One of the reasons I keep rapping is knowing that when I eventually catch fire, everyone can look back at my discography and see the beautiful progression of an artist that should have had his orchids, roses and daisies a long time ago.

— my father’s name (@McKinleyDixon) October 3, 2023

Beloved! Paradise! Jazz!? is out via City Slang Records.