In June 2016 a so called majority of the United Kingdom’s eligible voters decided to vote for the withdrawal of the UK from the European Union. What started more than 30 months ago as a complicated bureaucratic act, under inclusion of many different parties, nationally as well as internationally, is planned to find its manifestation on this year’s March 29 with a defined exit day.

On a warm October day in 2018 we met the British musician and producer Matthew Herbert in Leipzig, right between one of the rehearsals for his Brexit Big Band Project, in the middle of the Leipzig Jazz Festival. For his work, focussing on the emotional and highly political process of the so called Brexit, Herbert decided to reactivate his acclaimed Big Band concept, which saw already two releases in 2003 and 2008.

This time planned as a two year collaborative project right across Europe, it will celebrate the artistic and musical collaboration and communities across national borders. Besides different concerts in different places Herbert also used the collaborative time to record through rehearsals and concerts for an upcoming album release of his Big Band, scheduled for the very same March 29.

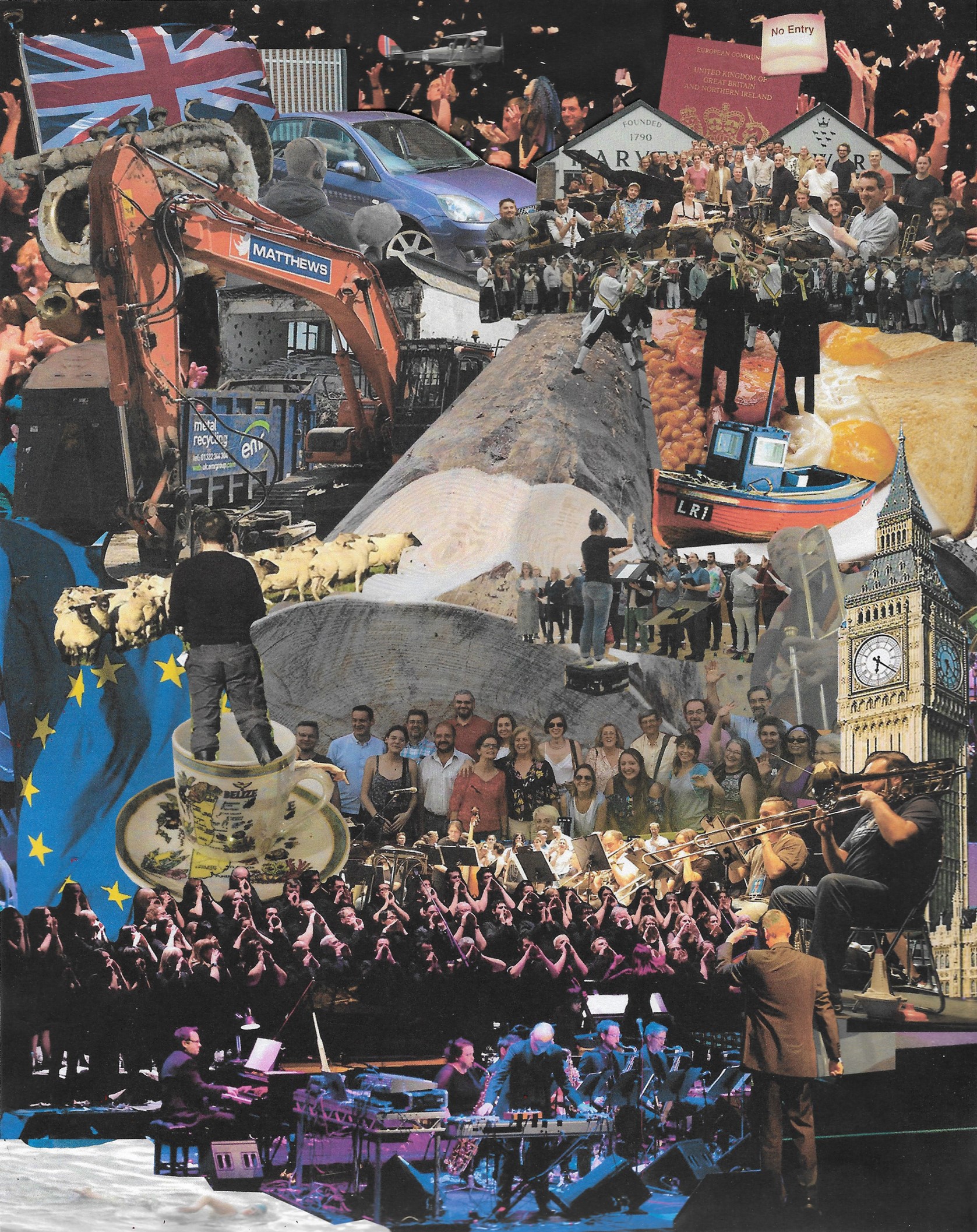

Illustration by Stefan Ibrahim

This isn’t your first Big Band album, we saw two brilliant releases in the past. This time the situation slightly changed. You decided to work over two years with different musicians from Europe. So it was the whole Brexit issue that brought you back to the Big Band concept?

Matthew Herbert: Yeah, I think so. I like the idea, that in a Big Band, it’s like a metaphor for how we should organize society. Which is every individual does their part and when they come together that makes something really unique and interesting and bigger than themselves.

For me I really liked that about a jazz band in particularly, cause in an orchestra you maybe have 25 violin players who playing the same line but in a Big Band its all individuals, playing their own part. And if the trumpet player plays a B flat and anybody plays a B natural then it fucks up from everybody else. So i like the metaphor.

I also don’t make my own trousers but somebody else does, and should be paid for properly. In exchange I can give them some strange music (laughs), and hopefully there is some connection somewhere.

Matthew Herbert and singer Rahel Debebe-Dessalegne (Source: YouTube)

So since the Big Band is surely is the biggest way of having a band, it also brings the biggest challenges?

Yes, when I was 14 my sister had a Big Band, so this actually the first band I was in. It’s really addictive, you have to be a little careful and that’s one of the reasons I stopped. You come on stage and when it’s swinging it sounds incredible, and it’s all acoustic. It’s way more hardcore than Heavy Metal or Rock because there are no amplifiers, it’s just the people blowing air down pieces of metal. So when it hits you it’s like nothing else.

It’s also hard to write new ways of working with a Big Band because its expansive to rehearse and there’s only so many ways you can combine these textures. You can obviously do infinite numbers of things with it but still you can’t make it sound like a drum machine or like a trump or like Angela Merkel.

That means you have a classical music education to which can you come back right now?

Yes, I stopped when I was about 18. I did theatric university instead of music. But as I said, I think it’s a trap. Because I think the future of music is music made out of pigs and cities and people and glasses of water and furniture. Because that’s the revolution in music, we can make music out of anything now, we don’t need instruments. So the instruments are just distraction, but the problem is they are still amazing. For me that’s difficult, I got asked to write orchestral music and in an orchestra you ask everybody to play a C Major chord and you can sit there for 20 minutes and this acoustic, this movement of air acoustically is so beautiful,. But I can say it’s a trap, it’s not the future.

What does your sister say, when she sees how you’re rework the usual Big Band concept today, while mixing electronics with the acoustics for example, instead of playing it classy?

She doesn’t do music anymore so I think she’s a bit jealous. But it was interesting, I used to play Glenn Miller compositions from World War II, one of the pieces was Moonlight Serenade, probably the most famous Big Band music from that period. And I started playing it in 1984, when the generation that fought in the war was still alive, they were elderly but still alive. When I used to play concerts the whole atmosphere in the room completely changed. Even now, talking about it, makes me feel very strange. All these people that fought in the war stood up and started dancing with each other and all the laughter had stopped and it was just about remembrance. And I will doing it on this record, I will do a version with a German band playing it and this is also about remembering.

Remembering that one of the reasons for the EU was because of the war and it’s so important that the value of Europe is we are friends, we are not enemies.

And is everything you gonna play with the Big Band now new compositions?

Today? No! It’s very difficult because this project is dated two years and is really depressing actually. I think it’s really important as well that there is some optimism and some spirit of activism. Sometimes if things are to heavy you don’t feel empowered, you feel drained. So it’s important to me that these shows a people-still-go-out-feeling, like they have some energy and it’s not just bad. So we do some of the older stuff towards the end.

‘Why the fuck should I give up my country?’

Coming from kind of a subcultural music scene, speaking of house music, techno clubs and so on, have you mentioned some shift into high culture now, when playing theaters, operas or jazz festivals at all?

It’s nice to be here. The first gig, I’ve ever did with my own Big Band was at the Montreal Jazz Festival in 2001. I think I’m getting old as well and I like to play a concert at 8 o’clock on a Wednesday rather than playing at 5 in the morning at Berghain. I just feel awake and connected. DJing in electronic world, late at night, can be really unsettling.

I think there is a really big shift. It has nothing really to do with me but there is a big shift when it comes to lots of more interesting classical music that is coming from people which don’t come from that world. For example Johnny [Greenwood] or Mika Levi alias Mikachu, she started composition but she’s more from a punk underground or hip hop world and is not interested in orchestras in that high art way. And I just think in ten years time there will nobody be going through a conservatoire in the high culture way, I don’t think that will exist because everything has been done with an orchestra, textually. Of course you can always write new melodies and harmonies but I think nothing is really surprising in that world. The surprise comes from juxtaposition or new sounds, different phrasing, different scales, different aesthetics. It feels sad to say that here in Leipzig, because of the long historical music tradition but that world is finished. That doesn’t mean it can’t may come back, but it’s finished. The economics of it don’t make sense, an opera house can’t pay a composer four years to write a huge opera like a Verdi opera or something, and then pay for the rehearsals. That’s not possible, I could say that will change, but it’s finished.

‘Art has to be flexible, the institution has to be flexible, the audience has to be flexible because now you can get Verdi’s opera on your phone alongside Katy Perry or whatever. There not a distinction anymore.’

In its 2018’s edition the Leipzig Jazz Festival focused on British artists and their artistic work in the light of the impending withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union. Right now there isn’t much out buzz from many musicians of your field, so your project seems to be right on time and more important than ever. Do you feel like a subcultural minority addressing it?

Well, there’s only 52% of the people who voted, and that’s not even 70% of the population. I don’t think it’s subcultural, it makes it sound cool but it’s not. The division in our country is huge, there is 100.000 hate crimes registered by the police last year so now there’s a lot of racism, there’s a lot of hate towards minorities. And this is caused by Brexit, it is made more worse by it. It’s a dark period for Britain.

I saw you talking on a panel discussion on Brexit, and through the participants the mood was quite melancholy yet calm, there was no anger at all. Have you ever thought about leaving?

Yes, my wife is from Hong Kong and she talks about it quite a lot. I did talk to her, I said maybe we gotta go to Germany, I’m in Germany once a month, coming here for 25 years, I’ve got a lot of friends here, there’s something fantastic about Germany.

But then it’s also like why the fuck should I give up my country? It’s like an ugly beast is coming to your house, do you get to leave the house or do you trying get the beast out? I think, if it was war, like in Syria, I would trying to go but here it’s not that bad yet. Also that government in really incompetent. It is not good at being a government. Well if you’re looking into America, where the right wing and the republican party are very good at being evil. There are very good at it, got a lot of money, got a lot of experience, they have no moral compass. And luckily in the UK they’re not that evil just yet.

The featured album by Matthew Herbert and his band – The State Between Us – arrives on March 29 via Caroline International. Find more information about the project as well as upcoming tour dates on brexitbigband.eu.