Melike Şahin has been touring for several years as the lead singer of Turkey’s biggest international band Baba Zula. In 2017 she launched her solo career and celebrated a huge success with her first studio album Merhem. Known as the modern “Turkish Diva”, Melike Şahin rose to fame in her home country and garnered international acclaim. The Turkish feminist and LGBTQIA+ movement echoed her songs with protest banners citing her lyrics.

AKKOR is her second studio album. It was recorded in London and produced by Swedish Grammy winner Martin Terefe. The melodies are as catchy as one would expect, with a bit of a disco twist. While Melike Şahin’s sound on AKKOR might attract new audiences, she remains supportive of her original fans. In the spirit of the album title, which translates to survival, she sings about finding the strength within to keep going. Her poetic lyrics, while inspired by personal stories, serve as analogies for communities struggling for equal rights in Turkey. Melike Şahin took time to answer a few questions about her writing and composition process, and about how she connects to her crowd.

Survival

NBHAP: I read this album is about survival, is that just personal, or do you get inspired by stories of survival of other people/women?

Melike Şahin: When I was writing my first album, I was focused on self-healing. The second album found its inspiration in my story but also in the stories around me. It’s a feminist album about survival and finding strength to continue even in dark days. Throughout the record, we are witnessing a woman. She just came out of a battle – we don’t know if she won or lost – she is scarred but she is rising again. Like a phoenix, she spreads her wings and flies. The album starts with a very epic and powerful song called “Sağ Salim” and ends with the very emotional “Burdayım”.

I wanted to emphasize that when it comes to survival, it’s not only about being powerful. It’s also about being fragile. I show my fragile parts to my audience too because without being vulnerable, no one can say that they are powerful.

It is also connected to the survival of previous generations. Trauma is transmitted from one generation to another and then to the next. There are some people who are able to say “no” to that transmission. There are some people who try to find another way to live. The people who did the work before me, these people are my inspiration. The generations of artists who used their voices to advocate for change. It is my job now to carry on. It is important to talk about survival, personal and collective. We need to share our stories, through music, social media, or with friends at the dinner table. All these stories inspired the album and motivated me to write.

Coming Together in Protest

Your lyrics have been picked up by the feminist movement in Turkey and appeared on protest banners. Have you drawn energy from that and has it influenced the record?

Nowadays in Turkey, the situation is a bit gloomy, to say the least. The femicide rates are increasing and we need to protest for basic rights and safety, while the authorities are trying to restrict us. Coming together to protest is powerful because it gives us the feeling that we are not alone. It gives me hope for my future and our future in general. I hope through feminist solidarity, we will gain our basic human rights at some point.

When I saw my lyrics being used at these marches and people feeling themselves and their struggles represented, I realized that this is what it means to be an artist. This is my job, right? To move people, to give them strength and the words they search for. I hope some of the songs on AKKOR can convey hope to people who listen.

As a musician and as a woman making music, have you felt the effects of repressions in Turkey on your songs or in your persona?

Yes, sometimes. My work can be deeply affected by the decisions of public authorities. As a public figure, voicing support for marginalized groups can lead to censorship. Some of my shows were canceled after I spoke publicly in support of the LGBTQIA+ community. Also, since the release of my first album, as my fame has grown, I’ve become more exposed to public scrutiny, which can be particularly harsh in Turkey. All this pressure has led me to self-censor during performances, limiting what I share with audiences between songs. If I speak too openly—even in interviews like this one—I risk further censorship and show cancellations. This situation doesn’t impact only me; I have a band and a production team, a group of about 50 people who rely on my work for their livelihood.

What advice do you have for those who face similar challenges?

I do not have advice except to surround yourself with people who are witnessing the same. I think in Turkey, everyone is feeling it one way or another. For me, it is not only about gender, but also economical. Surviving as an artist is a mission impossible. There is no governmental support or protective legislation for musicians. Beyond the music industry, it is hard to find motivation in these heavy times. Each and every day brings reports of new agendas or other big things happening. It is important to find spaces where you feel safe. For me, it is talking to my friends, especially women musician friends.

Voicing the Unspeakable

What inspires your songwriting?

I find a lot of inspiration in literature. Listening to music doesn’t give me the headspace to write. But when I read something powerful, I want to work on it. Some words and emotions just take me from my armchair to my table and make me write. Authors like Annie Arneaux, Deborah Levy, and Füruzan come to mind. I primarily seek out stories by women, as I feel I’ve reached a saturation point with narratives by men.

Can you tell us about your lyric writing process, do you write your lyrics as you would write poetry?

I mostly write songs when I lose my words. When talking doesn’t help, I write. I write to give a voice to the unspeakable, to the muted emotions. But songwriting is not part of my daily life. For instance, I finished the album like six months ago, and I haven’t written a word since. I had to take a break. Next week I’ll go on a me-time journey and have the intention to write a new song. If I don’t write a new song, the album is not finished to me. I need to know the journey continues, otherwise I’m not able to celebrate the release. Now it’s time to go back to the lyric writing process.

And do you write the music or the lyrics first, or in parallel?

I am obsessed with the melody of the words themselves. Their melody needs to be synchronized with the melody of the song. Sometimes both come at the same time. I always take notes of words to inspire me when I need inspiration for lyrics but when it comes to songwriting, melody and lyrics come at the same time.

Do you let your musicians improvise a bit on the melodies you write, or is everything mapped out in your mind before getting to the studio?

Usually, I give some keywords to my producers, and they make demos. After I listen to them, I decide on things, and we go into the studio. There is a creative and collaborative process, but it is not really improvised. The songwriting of the two records was very different: Merhem was recorded at home during the pandemic, and AKKOR was recorded live in London. It was a completely different vibe, very exciting, but also tiring. My focus period is a little short and my mind wanders, but while recording I need to be there 100%. It was also difficult to explain my lyrics in English to the other musicians. Initially, I wanted to take my band from Turkey with me, but they didn’t get a visa, so we worked with local artists. It was an interesting experience, and I learned a lot. Every musician brings different approaches and materials, which I find inspiring.

Like A Phoenix

Is there a story behind the visuals of the record?

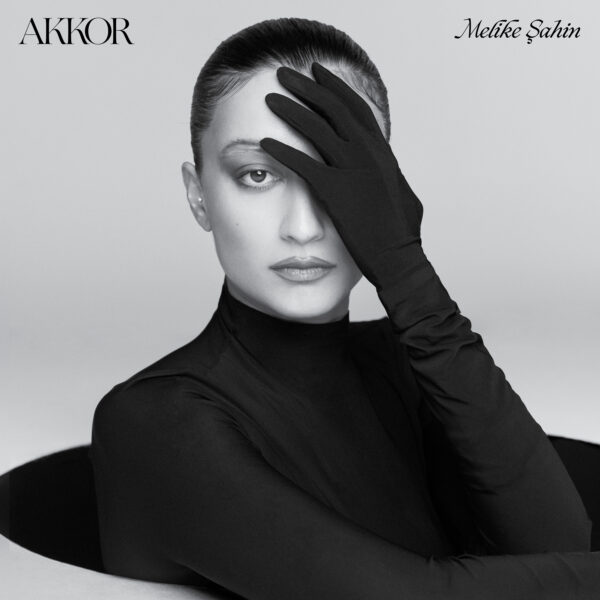

“AKKOR” Album Cover

Yes, the record cover has a particular meaning to me. I had an operation back then when I was younger, which left a very visible scar on my forehead. When I was a teenager, I hated it so much because everything was about appearance and a scar does not fit the beauty standard. But I came to own it as part of me. Like the phoenix rose from the ashes, with a scar. I love it now, and I think it is beautiful because it tells a story about me. On the cover, I wanted to emphasize the scar and show people that I am not afraid anymore to show myself fully. The cover is a celebration of that, and I am so in love with it. My creative director Oğuz Erel and the photographer Emre Ünal also contributed to this vision.

About appearances, on your IG, you post very glamorous pictures with amazing outfits and makeup, but also very natural pictures where your audience can see your face without any artifice. Is this a fashion statement, or a way to connect very honestly with your audience?

I am just being me, with no intentions or messages. I am an honest person, so I am being honest on my socials, too. But sometimes, the glamorous persona helps me to separate the performer from my daily life. Since I gained more fame in Turkey people recognized me in the streets sometimes. Just today, I went out in my very casual clothes and without makeup and a guy at the market was guessing where he knew me from. When I told him my name, he said he barely recognized me because I was so glamorous on stage. The two women I present visually are different from one another, a way to separate my private life from my stage life.

AKKOR by Melike Şahin is out via Gülbaba Records and Diva Bebe Records. Stay up to date with Melike Şahin via Instagram and her website.