Sheherazaad is not from here, nor from there. The singer and composer inhabits the inherent in-between of the diasporic experience – personally and musically. Having grown up in the US in a second-generation South Asian household, she was exposed to Indian and Western classical music. Sheher began formal voice education at age six and immersed herself in the music of Lata Mangeshkar and RD Burman. But still, Sheherazaad did not see her full identity represented. “The music of my origins did not exist yet”, she says. So, she created her own soundscape, diasporic at its core. It does not belong to any existing genre and centers an in-between state of being. Sheher calls this landscape of sounds Khwaabistan meaning Dreamland in Hindi.

Qasr is the second EP by Sheherazaad and, like her debut Khwaabistan, it poses questions of identity, migration, belonging, and imagined homelands. Reconnecting with her roots in Northern and Southern India, Sheher studied Hindustani and Carnatic music traditions and sings in Hindi and Urdu. The reduced instrumentation of Qasr highlights the impact of Sheher’s voice as she tells stories of feminine travelers, mother tongues, and the insanity of migration. Produced by the experimental Pakistani artist Arooj Aftab, the EP embodies its own niche as Indian contemporary folk.

A Fortress in the Dreamland

Shortly after the release of Qasr, I connect with Sheherazaad via video call. She is currently in Mumbai preparing to give workshops for female, femme, or non-binary artists as part of a residency in the West Indian city. Undisturbed by the noisy surroundings, we exchange ideas on identity, diaspora, and language.

NBHAP: Your first record is called Khwaabistan, which translates to Dreamland in Hindi. The new EP is called Qasr meaning Fortress. How did you get from the Dreamland to the Fortress?

Sheherazaad: Khwaabistan is the psychological landscape I needed to make the kind of music I wanted to create; music that is inherently neither here nor there. My music occupies this space of the so-called in-between worlds beyond borders and fixed precise identities. Khwaabistan was a way for me to come up with this world that does not exist yet. I needed it to have a location, a soundscape that I could be rooted in. Qasr is a fortress, a small part within that soundscape, and implies an enclosed space in which each song resembles a room. You open the door to it and a story with its own set of characters unfolds.

Tradition and Improvisation

To create that in-between sound, you experimented and improvised based on the sounds you already knew. How do improvisation and diasporic experience connect?

I think diaspora is at its core completely improvisational. The moment a person migrates everything – tradition, rituals, and way of life – is suddenly in flux. What can you do except improvise? You have to try things by reaching into an unknown – improvise. That is also how I work vocally. I studied many different forms of traditional, classical, and folk forms. There are structures and tiers in certain classical and traditional forms. But growing up in the diaspora, they are not always accessible to you. So, I have to reach into the dark, I have to improvise.

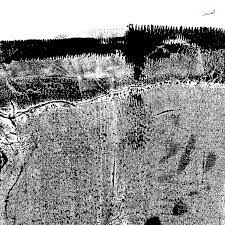

Cover artwork by Dinisha Dandwani

Dinisha Dandwani a textile artist made the cover of the album. It shows the imprint of a fabric, its texture leaving a grid of different densities in shades of black. How does the artwork connect to the record?

When you migrate and shift to the diaspora, there is always a sort of residue, which stays. It is a deep imprint of our heritage and roots. There are all kinds of stains getting left behind on us. So, the cover connects to this question of migration. What stays with you? What is the residue? The image also looks like something under a microscope. I think, my music does that in a way. I take these traditions and forms like folk, classical Western, classical Hindustani and Carnatic music, and try to contemporize them. Sometimes that requires putting them under a microscope and taking them apart to the skeletal structure.

Decentering the West

You mentioned that you studied classical music, the structures, and different traditions – Western and non-Western. Now you consciously decenter Western influences dominating much of the music industry. What did you have to unlearn and learn to make this record?

Growing up and through my early musical training, I was steeped in Western forms of music. I need to consciously examine how I work to avoid Western influences. It is a constant renegotiation and navigation of how I want to make music. Through studying the Hindustani classical music technique, I learned new ways of creating sound. In the beginning, I aimed for a complete return to the origin and became obsessed with completely rejecting Western vocal technique and English lyricism. But my music is inherently in-between, and I catch myself listening to Qasr and noticing Western techniques like vibrato. I learned that it is a process and for the rest of my life I can only hope to get closer to the traditional classical folk ways of singing.

“I had to learn to embrace my way of working and being, which is always in-between worlds. And it shows in pronunciation and vocal technique, and that is okay. I learned to accept and honor where I am at.”

Locality of Sound

Locality seems to play a big role in your creative process. The song “Dhund Lo Mujhe” (Search for Me), for example, is a theatric examination of migration and was born during a visit to your grandfather in Varanasi. You also traveled to India to study music and immerse yourself in it. How does your location affect the creative process?

Photo by Zayira Ray

Earlier this morning, I wondered: did I ever make music here [in India]? My music usually does not come from one place. For example, I write the lyrics in India, compose in California, but then record in New York. The entire creative process happens in this in-between. It is neither here nor there, and that in-between localities seep into my music on every level.

I also travel a lot and have a very physical reaction to changes in the environment. Initially, it is a feeling of shock. When I go from one place to the other, there is a different psychology, way of being, and persona that emerges. I have to have different souls. Navigating that also leads to music but there’s a time before that when I fall into complete paralysis and speechlessness.

It is interesting because your main instrument is the voice. It shifts with you as you move and switch language because you use your voice constantly in every new environment. I imagine you would experience this shock more intensely than someone playing another instrument.

Absolutely, the voice is as nomadic as the person whose voice it is. When I come back from India after a lot of linguistic study of Urdu and Hindi, having absorbed the languages, and I arrive in New York, suddenly I am forced out of it. I have to put all that into an ice box and hope it is still alive when I take it out. There’s no way my surroundings don’t feed in vocally. Just like me, my voice is constantly in flux, oscillation, and osmosis.

Lusting for A Mother Tongue

You sing in Hindi and Urdu, and you study their linguistics. How do those two languages connect for you, and what emotional connections do you have to Hindi and Urdu?

This is a profound question because the region of South Asia has a lot of perceived and actual conflict. That seeps into the language and linguistics. Often, we look at Hindi and Urdu as two different entities for political reasons. Saying that I make music in Hindi and Urdu is a phrasing in progress because it is actually not a binary. On a grammatical level, Hindi and Urdu are the same. It is the colloquial vocabulary that differs. This shows how languages are shaped by the politics of separation. I come from a Hindi-speaking family and community that is unfortunately still discriminatory toward Muslims. So, singing in Urdu is also a political statement and my way of reaching for reconciliation and love.

This is a profound question because the region of South Asia has a lot of perceived and actual conflict. That seeps into the language and linguistics. Often, we look at Hindi and Urdu as two different entities for political reasons. Saying that I make music in Hindi and Urdu is a phrasing in progress because it is actually not a binary. On a grammatical level, Hindi and Urdu are the same. It is the colloquial vocabulary that differs. This shows how languages are shaped by the politics of separation. I come from a Hindi-speaking family and community that is unfortunately still discriminatory toward Muslims. So, singing in Urdu is also a political statement and my way of reaching for reconciliation and love.

Singing and speaking Hindi is like soil coming from my mouth because I have an ancestral relationship with the land and the language. In the diaspora there were always bits and pieces of Hindi floating around; my father speaking on the phone, a film. I absorbed Hindi, but I do not speak it like a native. I speak it from a diasporic perspective. People in the diaspora, we often speak like children when we speak in our home language. This is difficult because there is a lot of shame and stigma attached to speaking in a ‘broken accent’. You need to understand that and own where you are at.

Qasr by Sheherazaad is out now via Erased Tapes. Follow Sheherazaad on Instagram or her website.