Hasn’t there everything been said about Bob Dylan already? Well, probably, but why not go for it one more round? Ever since appearing on the scene in the early 1960’s with his self-titled, hard-edged debut, the self-declared “song and dance man” and one of the greatest living American songwriters has somehow managed to become a “reluctant hero”, the patron saint of folk music who gave the world songs like The Times They Are A-Changin’ and Blowin’ In The Wind, which would embody the spirit of the social revolution of the 1960’s and put him on a pedestal he never really wanted. On top of that, the man is a fairly recent Nobel Price for Literature laureate against his own will – how else would one explain the absence of the songwriter around the time of the ceremony, not to speak of apparently plagiarising parts of his acceptance speech later on?

“A song is like a dream, and you try and make it come true. They’re like strange countries that you have to enter.” (Bob Dylan – Chronicles)

It may just be that Dylan himself has come to be as elusive as the phenomenon of folk music itself, that time and again I feel the need to turn back to his music. Regardless that I have serious trouble grasping his work after the mid-70’s, not to speak of his apparent vocal mediocrity, which might people lead to judging him as overrated, he embodies something that seems rare to be found these days: The romantic image of a restless artist on the move, with “no direction home” and yet, in all his ambiguity, a performer with a heart for the singularity of the song and the worlds it is able to unlock for everyone who listens closely.

Blurring the lines

As much as Bob Dylan’s beginnings cannot be seen isolated from the folk movement of the 1960’s, most notably represented perhaps his own idol Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, or the likes of Joan Baez and Joni Mitchell, his true achievement lies in him overturning the folk culture as a communal voice – passing over songs from generation to generation – and carving out original song material to go with the form of folk, tuned to the sensibilities of his decade. With an attitude of a modern poet and ready to fuse his lyrical prowess with the uniting power of a folk song, this move not only heaved folk music out of its dusty corner, but helped blurring the lines between literature and music significantly – widening both art forms and reminding them of their fundamental common ground.

If Dylan had stopped right there, he never might have been known as the artist eventually freely crossing genres of folk, rock, pop, gospel, country and jazz, fused by his means of turning political, social and philosophical lyrical touch – and he has a significant early share in the fracture of musical styles as we know it today. A most pivotal moment and remarkable illustration of this remains from the Newport Folk Festival of 1965, which later on has come to be recognised as initiation of “Electric Dylan controversy”, with Dylan performing his first concert with an amplified band, affronting a lot of die-hard folksies that would continue to boo him throughout the set.

How does it feel?

How does it feel?

To be on your own

With no direction home(Bob Dylan – Like A Rolling Stone)

While he was said to have “electrified one half of his audience, and electrocuted the other”, this might have just been the birth hour of folk rock and would lead Dylan to continue his electric phase spanning the mid-60’s records Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde, before eventually heading into more Country-esque terrain on Nashville Skyline (1969) and numerous other stylistic turns in the later course of his career.

A two-headed beast: Turning literature into music

Is Bob Dylan truly a poet?

Entire generations of interpreters and literary scholars have pondered over that question and while you would think that even highest literary awards would solve the issue once and for all, it is really the question itself that marks the problem. It reveals the narrow mindset that underlies the commonplace distinction between literature and music, between the high arts and the entertaining arts.

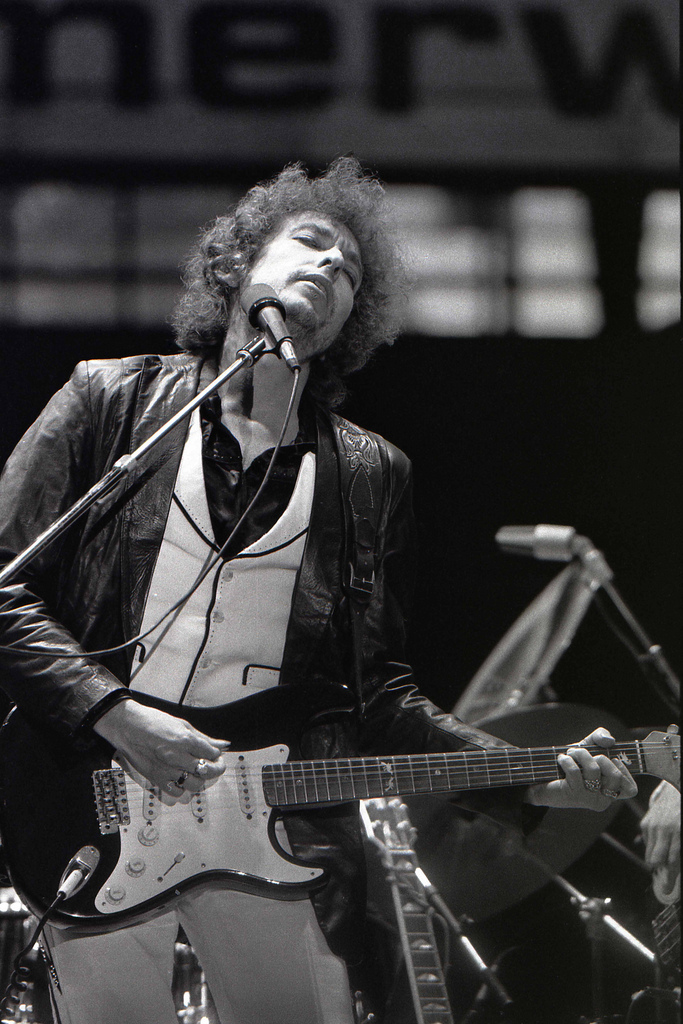

Bob Dylan in an electrifying mood back in 1978

It is needless to say, that Bob Dylan has never been a mere writer of books, but a penman of songs that seek to raise the sunken worlds of various ages and cultures and put them into a new, modern frame, creating something in between words and sound. His literary reference points span from the bible, Homer, Ovid, Shakespeare’s dramatic plays, up to the American romantics, William Blake, Arthur Rimbaud, not to mention the class of Beat poets such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg or William S. Burroughs, to whom Dylan has paid significant homage and with whom he shares the progressive poetic potential.

It is not really the question if Dylan is a poet, but to which extent one can really measure his contribution to the canon by means of mere literary criteria.

When Dylan aligns Shakespeare’s Romeo and Ophelia next to historical figures such as Albert Einstein and the writers Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot in Highway 61 Revisited’s eleven-minute-long epic Desolation Row, he is designing no less than a grand world theatre of history, myth, literature and fiction by means of a seemingly classic folk tune. Stylistically shaped in the form of a traditional folk ballad, it yet leans on T.S. Eliot’s modernist classic The Waste Land and condenses essential sentiments of modern entropy and urban chaos into it. Of course it is not poetry in its traditional sense, but something else than that, while poetic craft and original expression are gleaming through the mosaic narrative.

Praise be to Nero’s Neptune

The Titanic sails at dawn

Everybody’s shouting

“Which side are you on?”

And Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot

Fighting in the captain’s tower

While calypso singers laugh at them

And fishermen hold flowers(Bob Dylan – Desolation Row)

“All I can do is be me… whoever that is”

Of course, one can likely read too much into Bob Dylan, as he does provide a blank enough space for projections of all sorts. And especially when looking upon his later work I really wonder whether he is just toying around styles just for the sake of holding up that image of the ever-changing musician, never getting quite home. And yet, you can also look at it in a way, that Dylan has managed to free himself from any expectations the public might have – to that extent that even selling his entire back catalogue to Universal just last year didn’t cause the outcry that plugging in his guitar did back in the 1960’s. Well, how about that?

If you don’t think of him as an idol that has sold his core over the course of the decades, there remains the significant value of an artist whose only constant is that times are indeed changing, and that one has to adapt to the noise of time if you want people to keep listening. And when I try drawing the line to contemporary aspiring musicians, I’m thinking particularly about artistic (collectives) like Bon Iver or Ben Howard here, who also haven shaken off their folkish roots in order to tune their instruments to the sound of the here and now, I cannot help but feeling that Dylan’s aesthetics of chasing yourself to the extent of total alienation has influenced our times more than we probably are able to admit.

“An artist has got to be careful never to really arrive at a placewhere he thinks he’s at somewhere. You always have to realisethat you’re constantly in a state of becoming. And, as long asyou can stay in that realm you’ll sort of be alright.” (Bob Dylan)

Check out all editions of Andreas’ For Folk’s Sake series right here.