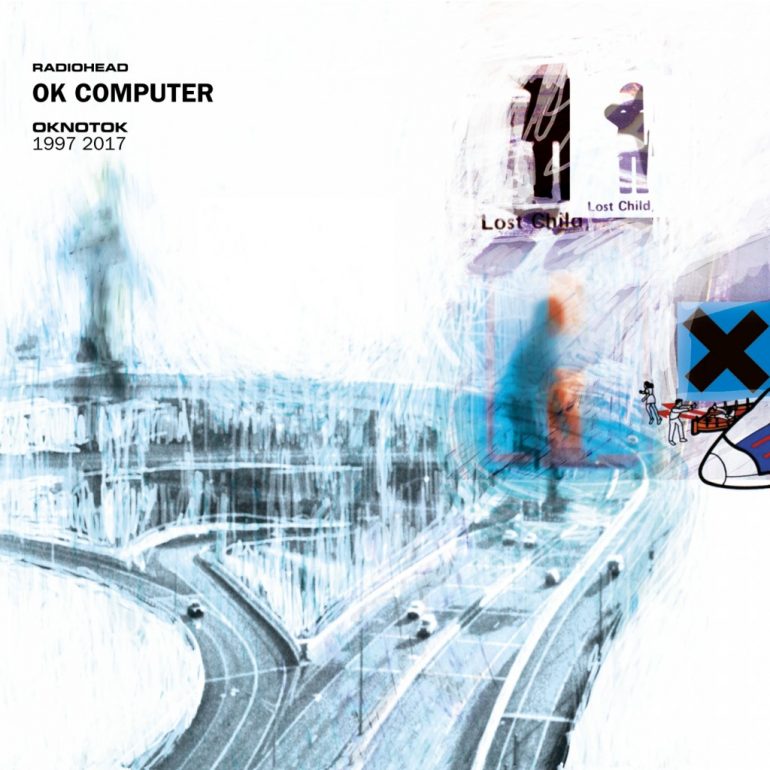

From today’s viewpoint, the story of RADIOHEAD sounds like an unlikely tale, full of strange occurrences and fortunate coincidences. Most bands consider themselves lucky if they have one smash hit or an exceptional album in their discography, or if they manage to carry on for more than a decade. Remaining in your original lineup for over 30 years is an accomplishment for any kind of band, let alone when you have released over half a dozen commercially successful and critically acclaimed albums and managed to stay relevant to this day. It’s for those reasons that most critics treat RADIOHEAD’s third album OK Computer, whose 20th anniversary was just celebrated with a special reissue entitled OKNOTOK, as an epiphany of sorts for rock music and music history as a whole – a record remarkably dense in its intellectual foundation and blessed with an exceptional level of musicianship, both in terms of production and songwriting.

However, great works are never the product of mere chance. Although in a way, the stars aligned on a number of occasions for Thom Yorke and the rest of the gang, following their second album The Bends, they managed to access their individual capabilities and seize the opportunities their major label backing could offer. In that sense, the making of OK Computer already foreshadows many aspects of RADIOHEAD’s unique dynamic that enabled them to produce both the ground-breaking indie rock of OK Computer and the avant-garde experimental rock music that followed. It also set an industry standard: by delving into the production side of music and taking matters into their own hands, RADIOHEAD were one of the first Britpop bands to consider recording an integral part of the songwriting process, shifting focus from composition towards sound – and by self-producing OK Computer together with Nigel Godrich, they also showed the way to go as a modern rock band in an industry that had yet to fall apart from the pressures of file-sharing, music downloads and streaming.

Continuous growth and development

Walking away from professional record studios alone can be perceived as a crucial point for the record. Instead of continuing the collaboration with John Leckie, RADIOHEAD decided to immerse into a field they had treated as a black box before. Buying their own equipment and working on the songs without the supervision of a famed record producer opened up entirely new sonic palettes for the band, which at that point had been a guitar rock band at the core. Without a deadline from the label, the band could focus on experimenting and honing their craft, exploring the possibilities that instruments like electric piano, Mellotron and strings had to offer.

It is not the only occasion where RADIOHEAD exhibited courage in doing things themselves: JONNY GREENWOOD, who is the only classically trained member of the band, started to put his long-grown love for orchestral music into practise when he composed a string arrangement for Climbing Up The Walls. It turned out to be the beginning of a success story: not only did he continue his orchestral work on tracks like Pyramid Song and Burn The Witch, he also went on to become a contemporary composer, writing scores and arrangements for several Paul Thomas Anderson movies and artists like FRANK OCEAN. Greenwood’s contributions to RADIOHEAD are at the forefront of their sound, be it in the form of an ondes martenot melody or an entire music sequencing programme.

Creativity through obscurity

With their minds ripe for experimentation and a desire to innovate, the band quickly tuned their ears to whatever got in their hands. RADIOHEAD cited musicians as diverse as MILES DAVIS, ENNIO MORRICONE, BEACH BOYS and JOHNNY CASH as inspiration for their music, and that’s no surprise: the band members have always been open to new stimuli. Thom Yorke studied English and Fine Arts at Exeter University, where he also DJed, while other members of the band have taken degrees in literature and related subjects. In effect, OK Computer is a cluster of quotations, the work of people with sharp eyes and an obviously informed opinion. The claustrophobic ramblings of Fitter Happier would be unthinkable without Thom Yorke sucking up every piece of cultural debris he could find, using the tired clichés and worn-out phrases to express a deeply critical or even cynical perspective towards consumerism and modern-day society.

Neither would a song like Airbag have started the record in such a futuristic way, had the band not set out to recreate DJ SHADOW’s way of sampling by recording and cutting up Phil Selway’s drumming, which converted a remarkable, but underdeveloped song into a studio anthem. Although most of OK Computer essentially sounds like rock music, the experimentation involved in the creation of the album gave the band a starting point to reconsider both the creative process and the classical rock line-up. Along with the constant input of new music from experimental electronic, classical or jazz artists like APHEX TWIN, KRZYSZTOF PENDERECKI or CHARLES MINGUS, this became crucial in the making of Kid A and Amnesiac, both albums where songs were constructed in the studio rather than on a guitar. Removing band members from fixed roles led the group to instead focus on the songs, a sentiment that is reflected by Jonny Greenwood in his recent interview for Rolling Stone:

Jonny sees Radiohead as ‘just kind of an arrangement to form songs using whatever technology suits the song. And that technology can be a cello or it can be a laptop. It’s all sort of machinery when looked at in the right way. That’s how I think of it.’

Trusting their inner voice

Though all members of RADIOHEAD held strong opinions about specific decisions or the creative direction of the band, if there is one constant to their work, it is their unwillingness to succumb to outside pressures and external validation. After keeping EMI executives at arm’s length for several years, OK Computer marked the point where the band were able to follow their own vision without executive meddling getting in the way. However, it was not only the label’s expectations the band wished to avoid; years of touring and being marketed as an MTV rock star made Thom Yorke wary of the image that had been stamped on them. Their reluctance to trust public reactions to their new songs, a trait exhibited by many of their later imitators, including stadium rock band COLDPLAY, sealed the fate for some songs. Lift, a Britpop anthem RADIOHEAD played on their tour supporting ALANIS MORISSETTE, was quickly picked up by her fans, as Ed O’Brien recounts in an interview for BBC:

It was a really interesting song. The audience, suddenly you’d see them get up and start grooving. It had this infectiousness. It was a big anthemic song.

RADIOHEAD however didn’t want to have any of it, and it’s clearly audible in the version released on OKNOTOK. Though technically identical to what the band played live, it lacks the live version’s vigour and euphoria. In describing that ‘we subconsciously killed it’, O’Brien pinpointed what led OK Computer to become a modern day’s Dark Side Of The Moon instead of a Jagged Little Pill: RADIOHEAD had set out to reinvent rock music and cleanse it of its pretensions, and landing a radio hit would have only got in the way of that. Although they denied us a fantastic take on what turned out to be someone else’s breakout single, we should be grateful for them not to have taken that road.

Radiohead’s 20th anniversary version of OK Computer, entitled ‘OKNOTOK’, has just been released.

It features a remaster of the original album and its b-sides along with three previously unreleased songs:

I Promise, Man Of War, and Lift.